Planning for the Complexity of Addressing Population Health Issues

Coalitions are one of the three critical components

By Peggy Geisler, Executive Director, Sussex County Health Coalition

Published March 2018 - Delaware Journal of Public Health Volume 4 Issue 2

Population health is complex. The plans that often accompany addressing population health issues will frequently fall short if the planning, design and implementation does not account for that complexity. Planning for population health should include three core components. These core components consist of a theory of change model, a systemic framework needed for change to occur and a vehicle to deliver/facilitate the change.

Each of these three components are critical in driving comprehensive population health impact and a community should work to understand the landscape through real data, engage multiple partners and plan. The following pieces to assist with that work should include a theory of change, a framing model and a community based coalition. These vetted best practices when combined, provide the complex infrastructure needed to address population health comprehensively. The three key components for this article respectively include: (1) Social Ecological Theory of Change (2) Collective Impact Model and (3) Community Coalition as the vehicle for change.

This article will briefly outline the three key components and their roles. It will then elaborate on each component consecutively to give the reader a basic working knowledge of the components to ensure an understanding of why each of the best practices individually are impactful. In addition, this article will paint the significant picture of the community based coalition as the critical and effective means to deliver and address population health and provide a real Delaware state example for the reader.

The Theory

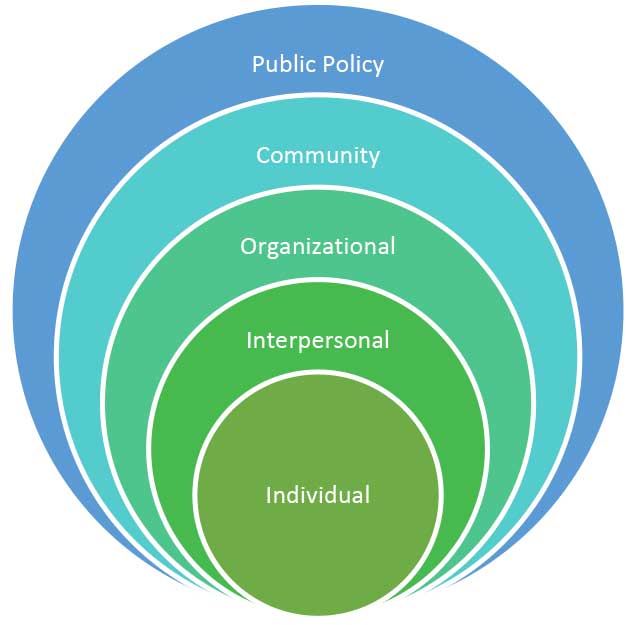

The Social Ecological Theory of Change (SETC) was coined by the Center for Disease Control and its violence prevention work is taken from the Social Ecological Model of McLeroy, Kenneth, Bibeau, Steckler and Glanz (1988) and takes into context all the factors that produce and maintain health and health-related issues. It allows for the community to identify layers that influence an individual’s behavior within his/her environmental context and helps better plan interventions and supports holistically. It does this by showing how social problems are produced, sustained and interconnected within a community (see Figure 1. The social ecological theory nested system (1988)).

This theory of change model demonstrates that an individual’s behavior is influenced by his or her beliefs, resources, family dynamic, community supports networks and the policy around his or her environment. An individual’s ability to navigate his or her health needs and issues can be complex and based on many factors that infl uence them. This theory has yielded a growing acknowledgment of the complexity of these systems, highlighting the need for more sophisticated community layered interventions and alignment to address the complexity. It is through these lenses, taken into context of one another that the community can move population health through alignment of strategies to foster change. Any one of these pieces can create a limited, siloed impact but it is through the more unifi ed and purposeful movement across all these layers that population health shifts. How do you ensure alignment through these layers and what is the most effective way to move a community together along these spheres of influence?

This theory of change model demonstrates that an individual’s behavior is influenced by his or her beliefs, resources, family dynamic, community supports networks and the policy around his or her environment. An individual’s ability to navigate his or her health needs and issues can be complex and based on many factors that infl uence them. This theory has yielded a growing acknowledgment of the complexity of these systems, highlighting the need for more sophisticated community layered interventions and alignment to address the complexity. It is through these lenses, taken into context of one another that the community can move population health through alignment of strategies to foster change. Any one of these pieces can create a limited, siloed impact but it is through the more unifi ed and purposeful movement across all these layers that population health shifts. How do you ensure alignment through these layers and what is the most effective way to move a community together along these spheres of influence?The Framework

The community needs to have a mechanism to frame this complex theoretical work and one such model would be the Stanford Innovations Collective Impact Model as described by Kania and Kramer (2011) in the Stanford Social Innovation Review.

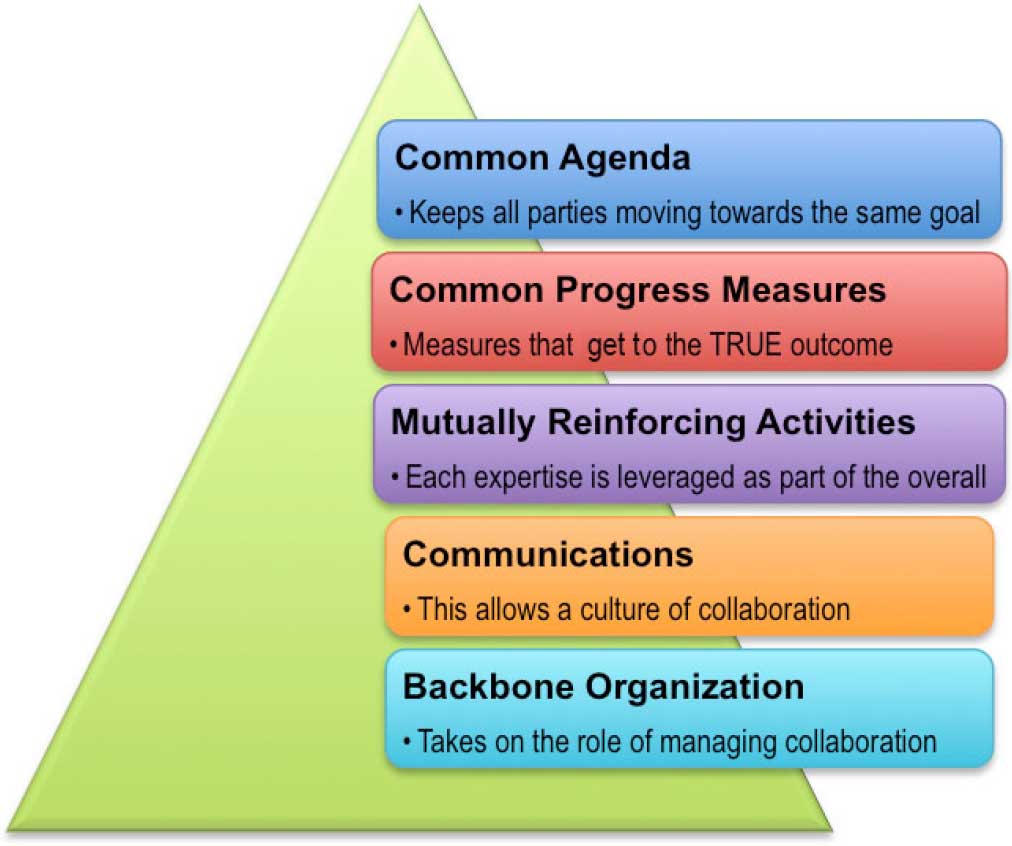

Collective Impact is a framework that allows for a cross sector approach for the operationalization of the Social Ecological Theory of Change (SETC) in real time. Kania and Kramer (2011) described 5 core components that are key to the core feature of the Collective Impact Model that provides the Alignment process across stakeholders (See below Figure 2. Graphic of the 5 key elements of collective impact (n.d.)) and these include: (1) Common Agenda (2) Common Progress Measures (3) Mutually Reinforcing Activities, (4) Communications, and (5) Backbones Organization/s that are key in addressing complex social problems. This framework is the tactical mechanism for the alignment piece while the Social Ecological Theory gives the theoretical rational behind the layers where alignment will need to occur, and the community’s strategies need to be integrated.

Collective Impact is a framework that allows for a cross sector approach for the operationalization of the Social Ecological Theory of Change (SETC) in real time. Kania and Kramer (2011) described 5 core components that are key to the core feature of the Collective Impact Model that provides the Alignment process across stakeholders (See below Figure 2. Graphic of the 5 key elements of collective impact (n.d.)) and these include: (1) Common Agenda (2) Common Progress Measures (3) Mutually Reinforcing Activities, (4) Communications, and (5) Backbones Organization/s that are key in addressing complex social problems. This framework is the tactical mechanism for the alignment piece while the Social Ecological Theory gives the theoretical rational behind the layers where alignment will need to occur, and the community’s strategies need to be integrated.This innovative yet structured approach (Collective Impact) and the layered strategies where interventions occur (Social Ecological Theory of Change) will not be able to be operationalized by any one entity or stake-holder.

The final piece that is needed to allow for the transformational approach is the development of a population health vehicle designed to be the outward manifestation of both the social ecological theory of change and collective impact. In this case and for this purpose, it is a Community Coalition.

A Community Coalition can be organized as the catalytic driver behind planning and operationalizing the Social Ecological Theory of Change through a Collective Impact framework.

The Vehicle A Community Coalition

The Community Coalition is the real-time mechanism that allows for the physical alignment of government, business, philanthropy, non-profi t organizations and citizens to achieve significant and lasting population health or other social change. The Community Coalition can be the entity that fosters and drives a Collective Impact Framework and the organizing mechanism across the identified layers in the Social Ecological Theory. The interdependency of the three provides a complex comprehensive approach in addressing population health and drives community health impact. A community driven approach such as a coalition allows for individuals, organizations and public policy to become aligned to drive change simultaneously. Change becomes more meaningful by providing an opportunity for those who are affected by the change to be part in guiding the change and developing the solutions that will be implemented. Coalitions empower the community and the individuals they serve to be part of the planning and decision-making process.

Butterfoss and Kegler (2002) developed the Community Coalition Action Theory (CCAT) which is a form of the Interorganizational Relations (IOR) Theory. A Community Coalition is a structured arrangement where all members from all sectors and different spheres of infl uence can converge around any community health initiative to organize, plan and implement strategies to create change. This is where the real work takes place by the people who are impacted the most.

The formation of the Community Coalition is the most crucial piece in operationalizing a population health initiative and it can range from taking on one targeted area identifi ed by the group or addressing more holistic landscape of needs. It can be geographically focused, issue focused, it can be both long term and short term, but its key component is a group of individuals who care about a need or issue that come together to collectively problem solve and impact the community.

The impact occurs through the coalescing of key stakeholders and their ability to create a shared comprehensive plan and work synergistically to execute the plan. This vehicle of delivery creates increased community resources and demonstrates significant return on investments while ensuring greater impact. The very nature of multiple individuals sharing knowledge, resources and experience in crafting plans and community based solutions allow for innovation, extended resources and improved outcomes around any social issue health being one.

Coalitions as a vehicle for public health and prevention based activities have been highly studied and utilized as an evidenced based practice over the past decade and coalitions have been found to be a key foundational component to help address complex social issues. The reason coalitions are considered the best practice in working on complex issues like health is because a coalition structure by its very nature is often layered with the stakeholders that physically represent or mimic the layers outlined in the Social Ecological Theory of Change. This physical manifestation of the theoretical model allows for more complex solutions to be identified and implemented in addressing population health and social issues. Community Coalitions allow for the most relevant, real-time and innovative approaches around population health to occur. In addition, coalitions can employ strategies simultaneously within the layers of the social ecological theory strata ensuring aligned community work.

The formation of a coalition often relies heavily on one key component of the Collective Impact model and that is the Backbone Agency. Dedicated staff, research and evaluation are key critical components that ensure long-term sustainability. Community Coalitions need a myriad of resources to start and maintain their efforts that include technical assistance and funding to support professional planning, resolve problems, create and implement innovative approaches, measure and evaluate and sustain the work.

The early stages of a coalition’s success hinges on the following according to Butterfoss & Kegler (2002):

- Inclusivity of a broad and relevant group of stakeholders

- Organizational structure and its development

- Evidenced based principles and practices

- Organizational capacity to plan, manage and implement

- Self-Assessment

- Sustainability

- Outcomes/impacts

Assessing a community’s readiness is critical. First, is the backbone agency a well trusted agency and on strong community footing? Does the community believe the agency is committed to the outcome? Is the agencies mission aligned with the work? Is that organization willing to be engaged for the journey 5 -10 years or is it only interested in a short term fix? These questions are very important when you seek to engage stakeholders. The answers ensure for stakeholders whether there is enough social capital and momentum towards addressing the issues. In addition, does the community have tangible resources in place? Tangible resources include leadership, political will, community resources that include financial and finally the stakeholder’s willingness and capacity to engage.

It is recommended that you or your community conduct a readiness assessment. This assessment should reflect the readiness of all sectors of the community including the backbone agency. The assessment itself needs to utilize a culturally competent assessment process that involves working with representatives from across community sectors in the planning.

During the assessment process the following will be crucial; (1) Understand how the population health problems are perceived among different sectors in the community; (2) Identifying the stakeholders that are already engaged in other similar initiatives; (3) identifying other multiple initiatives taking place and if they relate to what your coalition will be doing and fi nally, (4) what critical barriers are there to the engagement and support by stakeholders when it comes to the nascent coalition and its work.

The backbone agency needs to understand the landscape fully before launching. If all conditions are favorable, if the backbone agency has identified and engaged key champions and if a launch plan includes a theory of change, a framework to align and conditions favoring a coalition launch then the real work begins.

Model Health Coalition

The Sussex County Health Coalition (SCHC) was established in 2003 to engage the entire community in collaborative family-focused efforts to improve the health of children, youth and families in Sussex County Delaware. The organization is the backbone agency in Collective Impact Model and uses the SETOC as its lens. The organization has over 172 partner agencies who meet Monthly in task groups and quarterly as a whole to identify community needs and concerns. These committees work to align around targeted areas of need but verify the need through local data and stakeholder feedback. The Task Forces then work together to plan how to address the need from local or national promising practices. They do this by seeking support from strategic partners to address the need. The backbone agency in this case the Sussex County Health Coalition (SCHC) assists in helping foster the implementation of strategies, programs and or collaborations to ensure the interventions are completed with fidelity. The committee and the organization through technical support ensures metrics are recorded and outcomes are reported to the stakeholders and Task Forces when a change in the environment, service or individuals occurs.

SCHC created a Behavioral Health Task Group several years ago in answer to a growing need and concern by partners. The Behavioral Health Task Group (BHTG) current partner membership and monthly attendance ranges from 22-30 members. Those members identified Mental Health access as a critical need for children in Sussex County through a stakeholder forum. This coupled with local data presented by the Delaware Rural Health Initiative was the spring board to planning. The BHTG group set out to target access to services for school age children and youth one of the largest needs identified. They reviewed best practices, located a replica table strategy and put together an initial plan to replicate that strategy in Delaware. The organizations leadership worked to help securing funding through local providers who had an interest in that work and included, Discover Bank, Highmark Foundation and now Arsht Cannon fund. The School based Mental Health Collaborative was formed and is currently sustained over three and a half years later. This group has been able to ensure that four School Districts serving close to 15,000 youth have built a comprehensive Behavioral Health infrastructure within each district that has allowed for the systematic early identification and referral for youth who demonstrated a Behavioral Health need. Increased service providers in the school districts to reduced wait time for Behavioral Health services from 2.5 months to less than two weeks and increased provider capacity significantly in Sussex County. The model has allowed each district to collect real-time data and utilize that data to inform programming, policy and allocation of resources to meet the student needs. The districts have doubled the number of children being identified and receiving treatment. In addition, each district over 4 years have been provided minimal financial support but has also been able to sustain the services formed. Early data shows that this work is creating impact in school climate and academic performance in both Indian River and Woodbridge school districts who are model programs. This is just one example that a Community Coalition can have when stakeholders work together to identify issues in their community and when they work together to solve them. If you would like to learn more about Sussex County Health Coalition go to www.healthysussex.com.

Setting up a Health Coalition

A key backbone agency should work with an identifi ed champion or champions of a few key stakeholders. Hiring and supplying the nascent group a person well versed in coalition development to provide technical assistance and administrative support is crucial. The role of this staff person is to assist with bringing the key stakeholders around the table to develop the coalition’s initial organizational strategic plan and to identify the initial process for developing the community plan. It will be important to identify a vision as a coalition around the population health issue/s you seek to impact. Then a mission statement should be formed for the group along with core values. This will set the framework for the rest of the coalition’s work. This framework and the infrastructure will help drive the community based planning approach now and well into the future.

The infrastructure based on a strong theoretical framework that includes a backbone entity, a well-organized group of champions, and a clear, relevant plan is the foundation that allows for a coalition’s success. This, however, is only the beginning. Initially the Coalition must ensure timely small wins that allow for participants to practice working together in an aligned way and experience collaborative success. This increases the momentum of stakeholders and solidifies their commitment while often creating additional participation by other stakeholders. The early win is the first level of sustainability for a coalition as it demonstrates the potential of this model must to both the backbone funder and the stakeholders engaged. This allows for all involved to become more deeply committed and entices others to be part of the work. This is a shift from a conceptual organization to one that transcends a cooperative relationship to one of true collaboration that is purposeful. Purposeful collaboration fosters interdependence amongst participants such as funders, providers and consumers who are actively engaged for a shared good.

The more the cycle of planning, doing and achieving occur on both a small scale and larger scale the more the level of trust and purposeful collaboration continue. The framework of Collective Impact ensures this along with the organizational structure. If the aligned activities are layered in the Social Ecological theory levels the more likely the wins start to add up and moves an initiative momentum forward collectively.

Planning for a healthy community is complex, work. Complex social issues cannot be solved with simple solutions. The solutions that will solve them need to be rooted in proven theoretical models with comprehensive framework like Collective Impact and driven by a vehicle like a Coalition. This work is a marathon, not a sprint, and is focused on changing policy, community, organizational practices and infl uencing families and individuals to healthier practices. It’s about changing landscapes that are inequitable and removing barriers. It’s about aligning more than communication and activities. It’s about all of us owning the Health Issues in our community and developing comprehensive solutions and the key to all the work is partnership.

References

Butterfoss, F.D. & Kegler, M.C. (2002). Toward a Comprehensive Understanding of Community Coalitions Moving from Practice to Theory. In R. J. DiClemente, R.A. Crosby, MC Kegler,

Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research Strategies for Improving Public Health (pp. 157-193).

Center for Prevention Research and Development. (2006) Evidence-Based Practices for Effective Community Coalitions. Retrieved from: https://humantraffi ckinghotline.org/sites/default/files

Collaboration for Impact. (n.d.).[Graphic Illustration of the 5 key elements of collective impact]. Retrieved from: http://www.collaborationforimpact.com/collective-impact/

Kania & Kramer, (2011) Collective Impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/collective_impact

McLeroy, K., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K., (1988) An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education and Behavior, 15.4: 351–377